Direct Democracy in America From the Colonial Era to the Present

Democracy as practiced in the United State mostly follows the representative approach. This means that instead of every citizen voting on every law, we elect officials to make decisions for us. These representatives are supposed to listen to public opinion, and if they don't, we can vote them out in the next election. This system is how most democracies around the world operate.

But America has always had a mix of another kind of government: direct democracy. This is when citizens vote directly on laws and policies themselves, without a representative in the middle. You see this frequently in state and local ballot measures, where people put issues on the ballot by petition and then vote on everything from taxes to new laws. While the U.S. is and will likely remain a representative democracy at the national level, the idea of citizens having a direct say in their government is a core American value that persists in the current century.

The tradition of direct democracy goes all the way back to the country's start. In colonial New England, towns held "town meetings" where all eligible male citizens would gather to debate and vote on local laws, taxes, and spending. It was a pure form of direct democracy, born from the need for these early communities to govern themselves. These meetings, even though they only included a small group of people at the time (males only, usually members of the church and owning property), set a powerful precedent for citizens to be directly involved in their government.

As the country grew, it became impractical to have everyone vote on every issue, given the communications and transportation technology of the day. So, representative government took hold. But the spirit of direct democracy didn't disappear. During the American Revolution, committees of citizens would sometimes ask for public input on important issues. And when the U.S. Constitution was being created, it was ratified by conventions of people elected by the public, not by representatives in Congress. Even the founding fathers, who favored a representative republic to prevent a "tyranny of the majority," understood that the ultimate power rested with the people.

In the 19th century, direct democracy took a back seat. But it came roaring back in the late 1800s and early 1900s during the Progressive Era. People were fed up with political corruption and big corporations controlling politicians. They wanted to take power back. So, they created new tools of direct democracy:

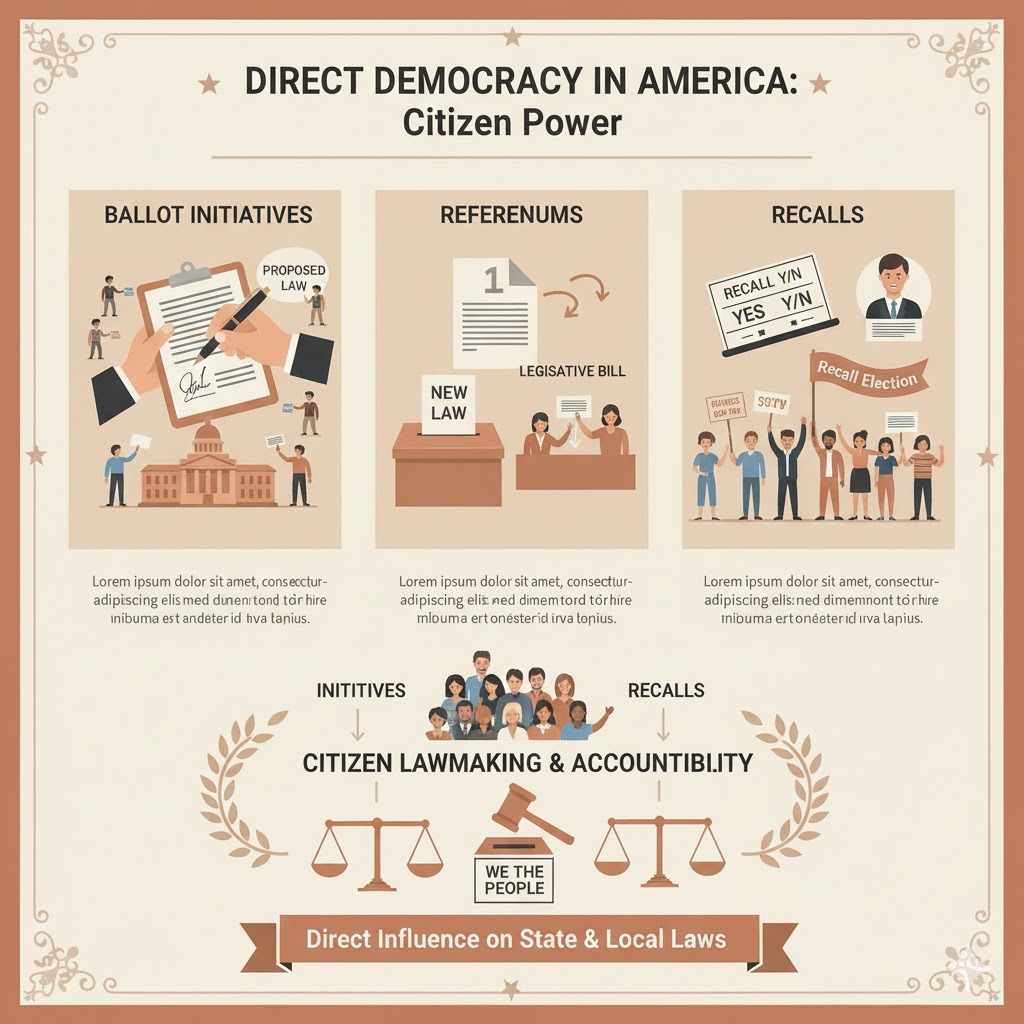

The Initiative: This allows citizens to propose new laws or constitutional amendments and get them on the ballot for a popular vote.

The Referendum: This allows citizens to approve or reject laws that have been passed by their state legislature.

The Recall: This gives voters the power to remove an elected official from office before their term is up.

These reforms, championed by people like Oregon's William S. U'Ren and Wisconsin’s Robert La Folette, were designed to give citizens a way to bypass unresponsive politicians and special interests.

Today, direct democracy is still very much alive, especially at the state and local levels. We use initiatives and referendums to vote on a range of issues, from legalizing marijuana to setting tax rates. Supporters say these tools make the government more responsive and give the public a voice. Critics, however, worry that voters aren't always well-informed on complex issues, that wealthy special interests can dominate ballot campaigns and that a simple majority can sometimes trample on the rights of minorities. While some states have deliberately made these processes harder, they remain a key part of our political system. The recall, while not common, is a powerful tool for accountability, as we've seen in several high-profile recall votes recently.

With modern technology like computers and the internet, it's easier than ever to conduct direct democracy on a national scale. You could argue it's even easier to hold a nationwide vote today than it was to gather people for a town meeting in the 1700s. While there's not a lot of support for moving to a national direct democracy right now, the idea could gain traction if people feel their representatives aren't listening.

In the end, the United States is a mix of both representative and direct democracy at the state and local level and democratic institutions are representative at the national level. From the town meetings of colonial New England to today's ballot measures, the idea that the people should have a direct say in their government has always been a powerful force. The ongoing push and pull between these two forms of democracy shows that the American democratic republic is always evolving, searching for ways to use democracy that balances decisions by leaders with the direct voice of citizens.