A Guide to Federalism: How Power is Shared in America

The United States was founded by thirteen individual colonies, each with its own interests and jealousy of sharing power with the others. The new nation needed to create a national government with considerable power to regulate the commerce and foreign interests of a growing country while still respecting the interests of the colonies and convincing them to ratify the new constitution. To achieve this, the founders created a unique for its time system called federalism, a division of power between a national government in Washington D.C. and the individual state governments and their local governments.

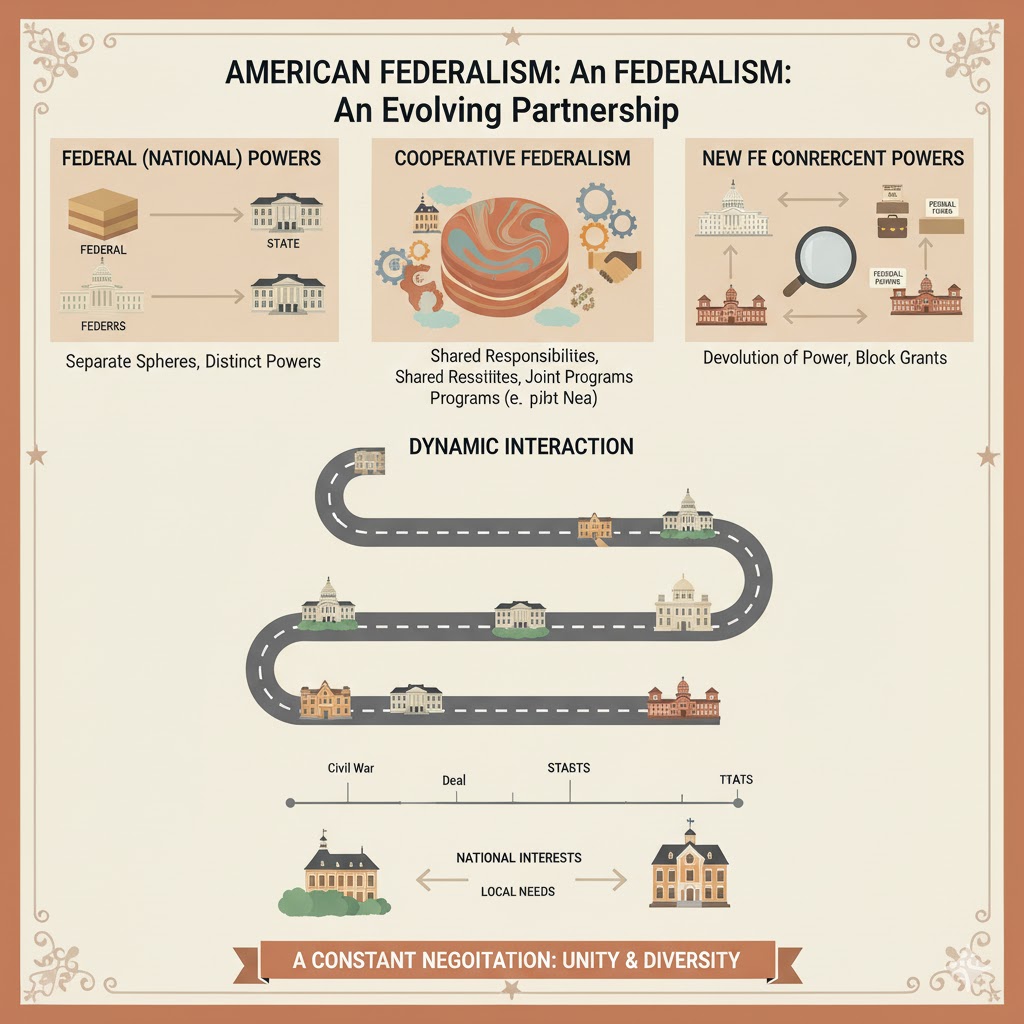

From the beginning, many powers were reserved to the states.Over the past two centuries, this system has evolved and continues to do so. It's a dynamic framework that has constantly adapted to the nation's needs. The power of various states and the national government has shifted over time as some states grew more powerful relative to others and as the national interest of the government grew. Let's take a look at how this dance between national and state power has evolved.

The "Layer Cake" of Early America

In the beginning, American federalism was like a layer cake. The national government and state governments had very clear, separate responsibilities that were clearly spelled out in the original constitution.

The National Government handled big-picture issues like foreign policy, national defense, and trade between states.

The States were put in charge of most of the remaining everyday matters, such as education, public safety and local roads. Local governments had their own fluid federal relationship within their states and that is still evolving today, with some states trying to reassert state power over all jurisdictions and challenging so-called home rule.

During this time, the states were very powerful and often experimented with new policies. While the Supreme Court made it clear that federal law was supreme in a conflict, the two levels of government mostly stayed in their own lanes. The Civil War did not fundamentally affect this power sharing arrangement since the Southern states that favored slavery (opposed by most Northern states) eventually pulled out of the union rather than compromise.

The "Marble Cake" of the Great Depression

The Great Depression of the 1930s finally changed the nature of this power sharing. The economic crisis was so widespread that individual states were powerless to handle it on their own due to lack of resources. This led to a era often called Cooperative Federalism, which was more like a marble cake—the layers were no longer separate but swirled together because Washington had the resources to deal with depression.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt's with the support of Congress, enacted New Deal programs which dramatically expanded the national government's power. Washington began sending money to states to help with everything from building roads to creating social programs. However, this money usually came with strings attached, giving the federal government more and more influence over state policies. This marked a major shift, making the two levels of government more dependent on one another.

Giving Power Back to the States

In the 1970s and 1980s, a movement called New Federalism (often couched in terms of State’s Rights) tried to push back against the growing power of the national government. Presidents like Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan argued that states were better at understanding and responding to the needs of their citizens.

The goal was to give more authority back to the states, often by giving them huge block grants—large sums of money for a broad purpose, allowing states to decide exactly how to spend it. This was an effort to shrink the federal government's role and renew focus on states' rights, though it never fully reversed the expansion of federal power from the New Deal and the U.S. role as an emerging world power.

Modern-Day Challenges

Today, federalism continues to evolve as we face new challenges. Issues like climate change, healthcare, transportation and immigration often require a coordinated response from every level of government. Home rule movements complicate this further. So does the varying interests of so-called blue states versus red states, with the former often supporting more national social programs and wanting Washington to pay a lot of the costs, resulting in a larger role for Washington.

While states still hold a lot of power, the national government often uses its financial influence to encourage states to act on national priorities. Debates continue over issues like unfunded mandates (federal rules that states have to pay for) and which level of government has the final say on certain laws.

In the end, federalism in the U.S.A. is a constant balancing act that responds to varying economic and social needs, strong political personalities and the ideologies of special interests. It’s a perpetual dance between the need for national unity and the desire for state and even local autonomy, showing how a system designed almost 200 years ago still must adapt and respond to continent-spanning superpower’s changing needs and ideologies.