Gerrymandering in U.S. Politics: Reshaping Democracy To Favor Those In Power

In American democracy, voting is incredibly important. In a perfect world, every vote would count equally and everyone's voice would be heard. Unfortunately, this goal has not been met largely due to a widespread and controversial practice called gerrymandering. This practice, legalized by the U.S. Supreme Cour, essentially lets politicians pick their voters instead of voters picking their politicians.

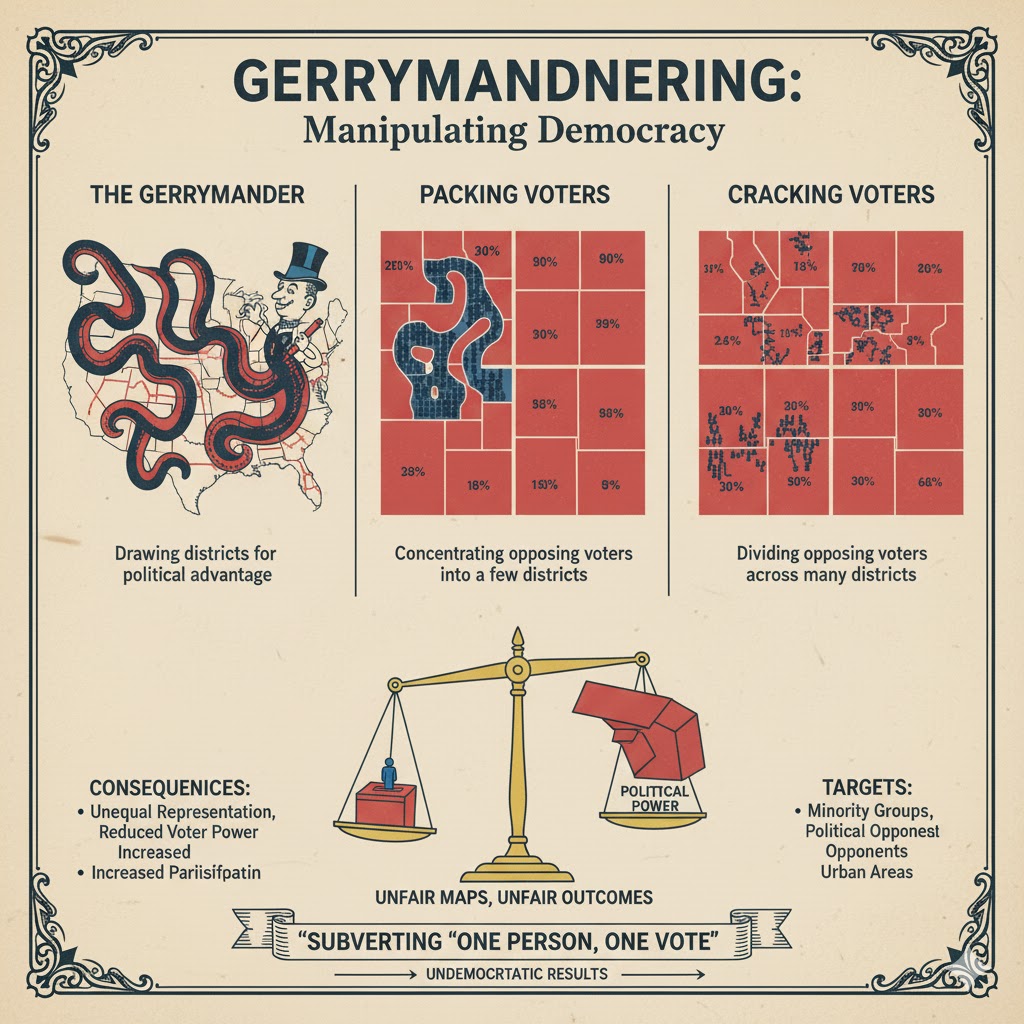

The term comes from a political cartoon in 1812 that showed a salamander-shaped voting district drawn by Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry. Today, it refers to manipulating the boundaries of voting districts to unfairly favor one political party over another (partisan gerrymandering). It can also be used to weaken the voting power of specific groups, such as racial minorities (racial gerrymandering).This isn't just a minor detail; gerrymandering deeply affects the fairness of our elections and often leads to results that don’t match what the public wants. For example, states like Florida and Texas have a close to even split of Democratic and Republican voters, as recent election results and polls show. Yet, both state legislatures are heavily controlled by Republicans, demonstrating the impact of gerrymandering.

At its core, gerrymandering is about drawing district lines to guarantee a certain political outcome. There are two main ways this is done:

"Cracking": This involves splitting up voters who support the opposing party and spreading them across many different districts. This makes sure they are a minority in each district, weakening their overall voting strength. Imagine a neighborhood where most people vote for Party A. To "crack" them, mapmakers might divide that neighborhood among several districts, each of which also includes a larger number of Party B voters. This effectively cancels out Party A's influence.

"Packing": This is the opposite. It involves stuffing as many voters as possible from the opposing party into just a few districts. The party doing the gerrymandering basically gives up on winning those few "packed" districts, but by concentrating the opposition's voters there, they make it much easier to win all the other districts. This strategy "wastes" the opposing party's votes, giving them huge majorities in a couple of districts, while the gerrymandering party wins many more districts with smaller majorities. In our "winner-take-all" system, if a candidate gets just one more vote than 50%, they win the seat, no matter how large their majority is.

The consequences of gerrymandering are far-reaching and harm our democracy:

Less Competitive Elections: When districts are designed to be "safe" for one party, the candidates already in office face little real challenge. General elections become predictable outcomes. This can make voters feel like their vote doesn't matter, leading to fewer people participating.

Increased Political Division: In safe districts, politicians are often more worried about pleasing their party's most dedicated supporters during primary elections than they are about working with the other side. They fear being challenged by someone from their own party if they appear too willing to compromise. This leads to more extreme political positions and makes it harder for our lawmakers to agree on solutions.

Silencing Minority Voices: Gerrymandering can reduce the voting power of minority groups, both racial and political. This goes against the idea of equal representation and can mean that elected officials don't pay enough attention to the needs of these communities. For example, by spreading out a concentrated Black population across several districts, their collective voting power can be diluted, making it harder for a candidate representing their interests to win. Similarly, Hispanic or Asian American communities might find their votes split across multiple districts, diminishing their ability to elect candidates who truly reflect their concerns.

Fixing gerrymandering is a tough problem, but several solutions have been tried:

Independent Redistricting Commissions: One popular idea is to create groups of non-political citizens or experts to draw district lines. These commissions are supposed to base their decisions on things like equal population size, how compact districts are, and whether they're continuous, rather than on political advantage. States like Arizona and California have used this model and it has led to more competitive elections and more engaged voters.

Non-Partisan Algorithms: Another possibility involves using computer programs or mathematical formulas to draw districts, aiming for maximum fairness. While this removes human bias, it can be hard to define "fairness" purely through math.

Court Challenges: Courts, both state and federal, sometimes step in to block district maps that are obviously unfair. However, what exactly counts as an unconstitutional gerrymander is still a hot topic of debate. In a key 2019 case, Rucho v. Common Cause, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively ruled that federal courts could not hear challenges to partisan gerrymandering, leaving it largely up to the states to decide their own boundaries. This decision has legitimized the widespread practice of drawing districts to benefit one party in state legislative and U.S. House of Representative elections.

Gerrymandering is a significant roadblock to having a truly representative democracy in the United States. By letting politicians choose their voters instead of the other way around, it distorts election results, fuels political division and can silence the voices of entire communities. While overcoming the political hurdles to reform will be difficult, it's essential to pursue fair maps if we are serious about practicing democracy in the United State. Only by making sure that our voting districts truly reflect the diverse populations they serve can the promise of American democracy—a government truly of the people, by the people, and for the people—be fully realized.